Internet-scanning U-M startup offers new approach to cybersecurity

Censys is the first commercially available internet-wide scanning tool. It helps IT experts to secure large networks with a constantly changing array of devices.

Enlarge

Enlarge

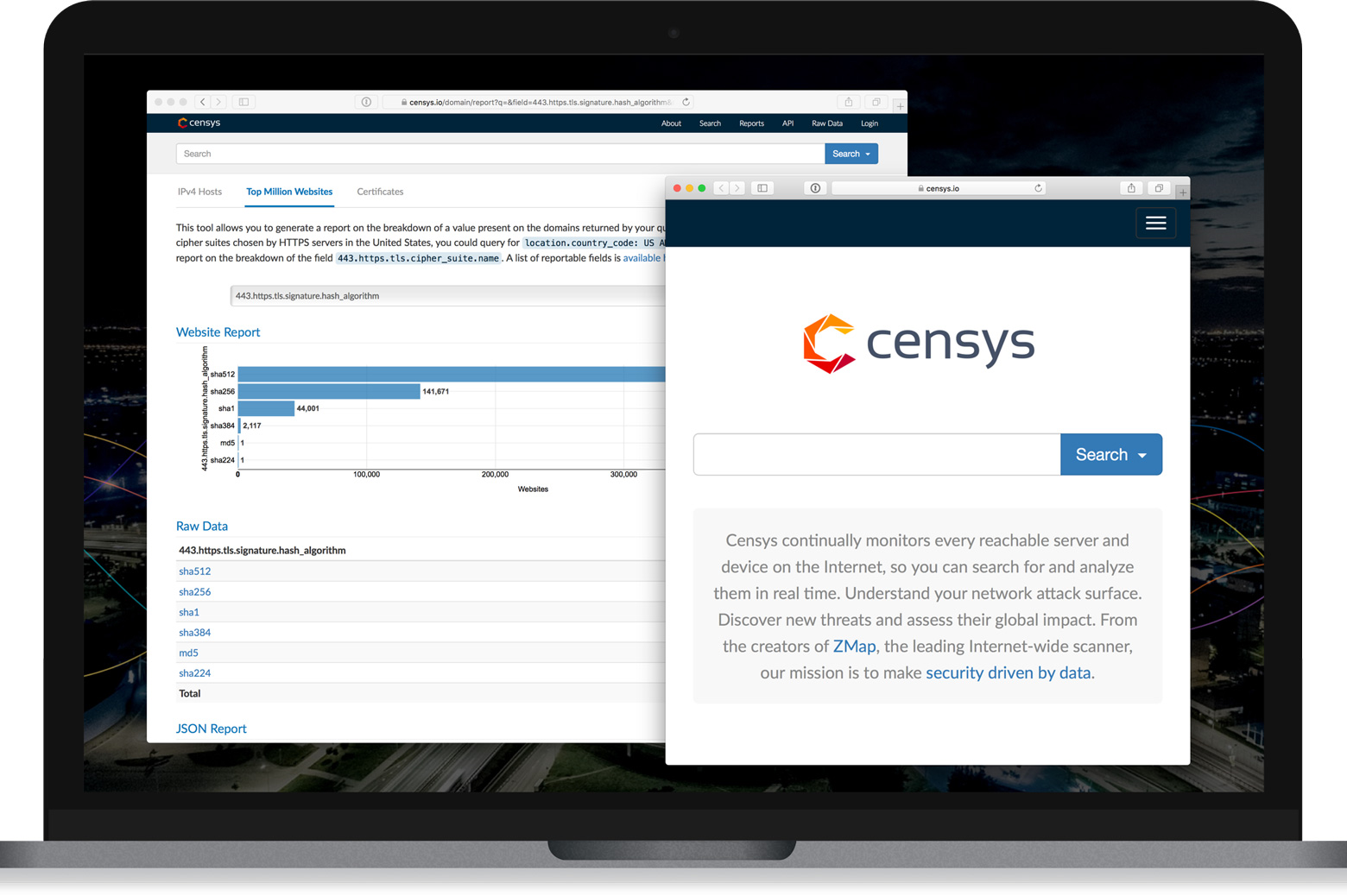

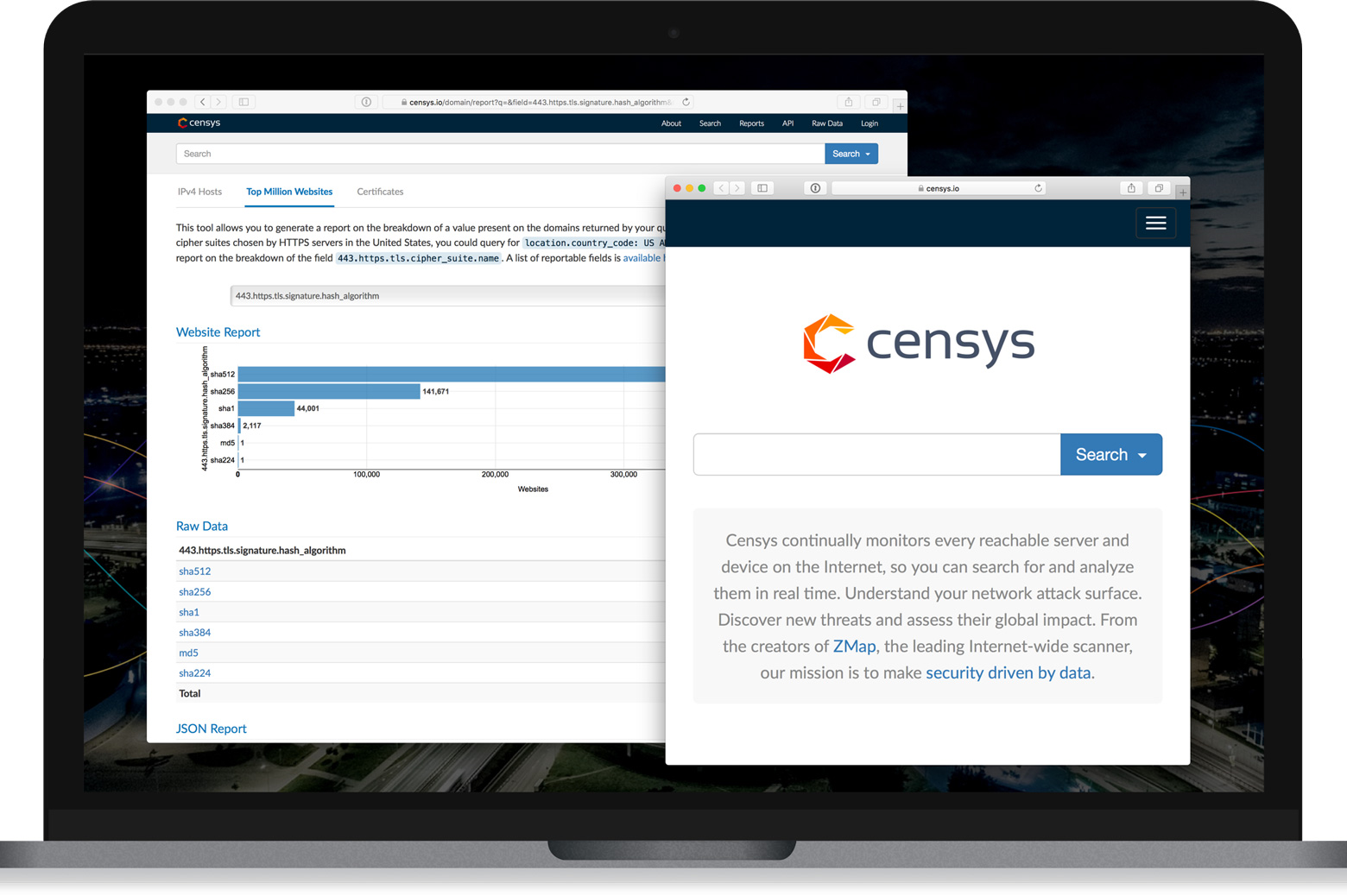

Rolling out what it’s calling a “street view for cyberspace,” Censys—a tech startup based on technology developed at the University of Michigan—has launched a commercially available version of its internet-wide scanning tool.

Based on technology developed in the lab of U-M computer science and engineering professor J. Alex Halderman, Censys continuously scans the internet, analyzing every publicly visible server and device. It uses the data that comes back to create a dynamic, searchable snapshot of the entire internet.

Censys could be an important cybersecurity defense tool for IT experts working to secure large networks, which are composed of a constantly changing array of devices ranging from servers to smartphones and internet-of-things devices. One unsecured device is all it takes for a hacker to break in, and there’s currently no good way for IT experts to get a comprehensive view of their own networks. Today, they must often battle hackers and other online threats without a complete understanding of their network’s vulnerabilities. Censys aims to change that.

“Network security doesn’t have to be black magic,” Halderman said. “So much of security practice is based on untested assumptions, but in fact security can be quantified and studied the same way we use data to study human health.”

Network security doesn’t have to be black magic.

J. Alex Halderman, EECS professor

Censys has been available for free to non-commercial users since it began as a U-M research project in 2015. During that time, it’s been used in hundreds of peer-reviewed studies and helped researchers better understand some of the most significant Internet security threats of recent years, Halderman said.

Over the past six months, Halderman’s team worked closely with the U-M Office of Technology Transfer to license the technology and form a new company, making it available to commercial customers. Now, IT experts can use it to search for every device on their domain and get back a detailed view of their public internet footprint, as well as analytics outlining vulnerabilities.

The data that powers Censys will also be available for license by companies who wish to build their own applications around it. Censys data will remain available free of change for non-commercial use by researchers.

During the scanning process, Censys performs a brief data exchange called an “application-layer handshake” with every device that has a public internet address. It then dissects the data that comes back, pulling out useful nuggets of information like protocol, device type, manufacturer, software version and age. Censys also has tools that can scan for specific vulnerabilities; the system is designed so that additional scanners can be added easily as new threats emerge.

Enlarge

Enlarge

Halderman explains that internet-wide scanning isn’t new—hackers have known about it for years. In fact it’s relatively common for them to use collections of hijacked machines called botnets to troll for vulnerable systems. In Halderman’s view, Censys levels the playing field by making global scanning data available to internet defenders, including IT professionals and researchers.

“It’s similar to Google Street View, where we’re gathering what’s already publicly visible and making it available in one place,” he said. “To extend the analogy, we just take a picture from the sidewalk. We don’t peek in the door, we don’t jiggle the locks.”

Any network that doesn’t wish to be scanned can opt out, though Halderman says such requests have been rare during the five years that the scans have taken place.

Censys is an outgrowth of the ZMap Project, a suite of open-source internet scanning tools that Halderman’s lab began developing in 2013 at U-M. While the ZMap Project tools remain freely available, Censys builds on them to provide an easy-to-use service that gathers and analyzes data automatically.

The company is based in Ann Arbor and has nine full-time employees. Censys CEO and co-founder Brian Kelly says that companies like Censys are helping to cement Ann Arbor’s status as a hub for tech security companies.

“It’s great to see that investors are no longer shy about investing in a company that isn’t in Silicon Valley, and the talent pool here is phenomenal,” Kelly said. “U-M in particular has been really helpful in creating an environment where we can take software products out of the lab and into the real world.”

The technology behind Censys is detailed in a paper titled “A Search Engine Backed by Internet-Wide Scanning,” published in the Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS) in October, 2015. The paper was authored by Halderman; former U-M computer science and engineering students Zakir Durumeric, David Adrian and Ariana Mirian; and Michael Bailey of the University of Illinois, Urbana Champaign.

MENU

MENU